Things To Do In Denver When You're Dead

by Speranza

Author's Note: Many thanks to all the usual suspects: shalott, resonant, and Terri. This story was written for the sga_flashfic "Left Behind" challenge and demonstrates my continuing inability to understand the "flashfiction" concept.

1

Rodney thinks that he can detect Sam Carter's well-meaning hand in the fact that they're put up at the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs (five stars according to travelsmart.com) rather than on base in Cheyenne Mountain. Everyone seems to take it for granted that they'll have people to see and things to do. "They've been in another galaxy, sir," Sam probably said, rolling her eyes, and the generals probably looked nervously at each other and agreed that, yes, the senior staff of Atlantis might well want to have a steak, or visit their mothers, or both.

This is how Rodney finds himself standing at the registration counter in the overly ornate lobby of the Broadmoor, being handed a key card for room 914. Beside him, Sheppard is looking around warily, like he expects a Wraith to jump out from behind a pink fluted column or a damask armchair. Further down, Elizabeth smiles as she signs something with a pen chained to the desk; Beckett's already taken advantage of the SGA's long leash, and has high-tailed it for the Highlands. Rodney doesn't blame him; compared to Pegasus, Scotland's a hop, skip and a jump.

"Gentlemen," Elizabeth says, nodding as she passes them. There's an unfamiliar gleam in her eye, a barely-suppressed excitement in her stride; it's obvious that she's going to be meeting someone. Rodney pauses to watch her disappear toward the bank of elevators, then turns back to the clerk to sign his own registration form; beside him, Sheppard palms his key card off the counter with a lopsided smile that looks friendly, but really isn't at all.

Sheppard follows him to the elevators without speaking, but frowns when Rodney presses the button for the ninth floor. Sheppard tilts his key toward Rodney; he's in room 916. Rodney nods just as the door opens, and then they're walking up the corridor with its ornate wallpaper and hideous pink-tinted lights. Their rooms are next to each other, but the doors are, thankfully, separated by a big chunk of wall. The small brass nameplate on the door next to his reads 912, and Rodney will bet dollars to donuts that it belongs to Elizabeth Weir.

"Catch you later," Sheppard says, and Rodney waves an impatient hand at him as he swipes his keycard and shoves the handle down when the light flashes green.

2

His room is awash with faux-luxury touches: the bed is unnaturally high and has too many pillows, there are white bathrobes and a million stupid little bottles in the bathroom but only a tiny little coffee machine and a single Ethernet port—not even wireless. Sighing, Rodney drops his bag and yanks off his jacket. Then he sits down and sweeps everything on the desk—hotel information booklet, complimentary notepad and pen, Colorado Springs tourist literature, idiot's guide to Ethernet—into the trash and sets up his laptop. Then he dials room service.

In room 912, the shower goes on. In room 916, the television.

Rodney begins to boot up various things he's working on; he likes cycling between projects, working on each as the mood strikes him. He finds that sometimes the answer to one problem comes to him as a distraction from another problem, and has learned to capitalize on that fact. He also takes a moment to crack the graduate student server at MIT, just to see what the kids are up to these days; the professors, he knows, are hopelessly mired, but the kids might do something worthwhile before their advisors beat their wackiest ideas out of them.

In room 912, a hairdryer is blaring. In room 916, the television is still going strong.

A knock on the door tells him that his food's arrived. Rodney's leaning against the open door and scrawling his name on the bill when Elizabeth passes behind the waiter, drop dead gorgeous in high heels and a tight-fitting blue dress. She glances at him and laughs, and Rodney realizes that he must be gaping. He snaps his mouth shut and shoves the bill at the waiter, who nods obsequiously and pushes the cart of covered dishes into his room.

Rodney eats idly, picking at the various dishes as he surfs his old online haunts, then has an idea about the matter displacement wave he's been trying to predict and works furiously until his back twinges. He pushes back from the desk, gets up, and stretches; he's been hunched over for—how long? Hours, he realizes, glancing at the clock—but he can still hear the murmur of the television from next door.

4-3, Rodney thinks before he knows what that means, and then he does know. It's hockey, and the score is 4-3; before that, it was football, final score 16-6; before that, football again, 32-14. He finds he's exhausted, and he strips down to his underwear, throws half of the pillows onto the floor, and switches off the light before getting into his too-high bed. In the dark, he falls asleep to the announcer's voice and the familiar metallic shushing of skates.

3

He knocks on Sheppard's door the next morning to see if he's going over to the SGC. Sheppard answers the door barefoot and in sweatpants, with his hair flat on one side and his cheek strangely chafed. Rodney, who's often woken up looking much the same, knows what this means: Sheppard fell asleep somewhere on his face. "Yeah, I—yeah," Sheppard says, sounding exhausted; he rubs at his bristly chin and says, "Give me a minute."

Rodney assumes that this means he should wait in his room, but Sheppard surprises him by holding the pneumatic door for him. Rodney instinctively puts his hand up, and by the time he realizes this commits him to coming inside, Sheppard's already drifting back into the room. The television, Rodney sees right away, is still on—ESPN, and some newscaster is giving post-game analysis, and then there's a slow motion replay of a bunch of guys in helmets crashing into each other. A quick glance shows four empty beer bottles with the labels peeled off, and a bunch of tiny crumpled foil packages of what Rodney immediately recognizes as vending machine fare: single-serve packages of Doritos, couple of Snickers bars, pretzels, chips. Sheppard is gathering up his discarded casual uniform when Rodney asks him what he had for breakfast; Sheppard shrugs, picks up an open can of Coke, and drains it, tossing it into the trash with a satisfying thump on his way into the bathroom. Rodney can't really argue with this because Coca-Cola (sugar, caffeine, instant energy surge) has always been the Breakfast of Champions, but he thinks about maybe asking Sheppard to order room service with him later on tonight.

They stop at Elizabeth's door on the way to the elevator, just for form's sake. She isn't there.

4

There's some kind of power struggle happening. Rodney's not central enough in the power politics of the SGC to know what it is, but still, he can smell it, and he becomes certain of it when he finds out that they've sent Sheppard away in the middle of the day with a multi-day leave pass. Rodney wonders if Sheppard will do a Beckett and hop the next plane for—well, wherever Sheppard's from, but when he gets back to the Broadmoor later that night, he can hear the television on in Sheppard's room when he passes it.

Rodney's changed and comfortable and in front of his laptop when his stomach growls, and it's only when he reaches for the room service menu that he remembers his idea of getting Sheppard to eat by ordering food with him. Sighing, he shuts the laptop, pads out to Sheppard's door, and knocks.

"Yeah?" Sheppard calls from inside.

Rodney rolls his eyes. "Housekeeping," he calls back, and when Sheppard opens the door, he's barefoot and in the same black sweats as this morning, only now he's wearing a faint grin.

"I could use some fresh towels," Sheppard says, and tilts his head ironically.

Rodney pushes past him, into the room, and says, "You could use some food that didn't come out of the minibar. I'm getting burgers, what do you want?" The television is on, still tuned to ESPN, and it's football again. Sheppard's desk is still covered with the hotel literature, and Rodney finds the room service menu, and hands it to him. Sheppard takes it, flips it open, and frowns down at it. "The fries were good," Rodney says, eyes drawn to the television again; he doesn't understand football, and hasn't ever wanted to waste time trying. He'll just order the food and go back to his laptop.

But then Sheppard looks up from the menu. "Okay, yeah, I'll have the same," he says, and then, handing the menu back to Rodney, "Do you like football?" and of course the only answer to that is, no; no, he doesn't. Except Rodney hears himself saying, "I don't really know enough about it," and then Sheppard is moving past him, eyes on the screen, hands waving in the air, and he's saying, "Okay, so look, it's simple, it's just like hockey, really. The goal is to move the ball to the opponent's end zone, and you can move the ball by either passing or rushing..." and it's five minutes before Rodney can stop him for long enough to get their food order in.

5

Sheppard's too deep in the game to get the food when it comes, so Rodney signs his name to the tab and waves the cart in; burgers, fries, beer. Sheppard pulls himself away long enough to claim his food and pop open a beer, and then he sprawls on the bed and eats French fries, mechanically dipping them in ketchup before putting them into his mouth. Rodney sits in the desk chair and puts his tray on the bed, eyes moving between the game (not nearly as complex as he thought, once he gets the whole concept of "downs") and Sheppard's obsession with it. At one point, Sheppard jumps up, yelling and nearly toppling his tray onto the floor, and when Rodney demonstrates his lack of understanding by failing to be suitably impressed, Sheppard darts to the screen and narrates the instant replay, finger tracing a line across the screen: the running back is moving rapidly through a channel between two groups of offensive blockers, running and running before he's tackled down to the ground. Rodney's pretty sure that wasn't a touchdown, but Sheppard swipes his beer off the nightstand and takes a long, satisfied-seeming swig.

6

"So, the SGC sent you home," Rodney says, dropping the words into one of the many long, slow moments of set-up.

Sheppard shoots him a sideways glance, but says nothing.

"Any plans for shore leave?" Rodney asks, and this time Sheppard doesn't even look at him; he just stares fixedly ahead at the screen.

7

Rodney goes back to his room after the first period of the hockey game that follows; Sheppard barely looks at him as he says, "Night," and waves his hand. Rodney's room is just as he left it, and it feels like home away from home—and all right, pot, kettle, because it's not as if he's gone anywhere or done anything that he wouldn't have done back (home) in Atlantis. Rodney shuts off the lights, then goes to the window and looks out over the twinkling lights of Colorado Springs: he could, he supposed, go visit his cat, if that weren't the most pathetic thing ever in the history of pathetic, or maybe he should go and see Schwartzman—though visiting your graduate advisor is even more pathetic than visiting your cat. Rodney leans his forehead against the cool glass and closes his eyes; he isn't interested in shopping, he'll download all the movies he wants onto a drive and ration them out over the long, long Atlantis nights, there's nobody he really wants to see. Still, there must be something here for him that there isn't back home—and all of a sudden, he's got it and he moves swiftly back to the desk, turns on the lamp, and opens the laptop. He googles "Colorado Springs philharmonic," and damn if there isn't a Colorado Springs Philharmonic, which, the website informs him, is the only professional orchestra of the Colorado Springs region. He's sure it isn't the Boston Symphony or the Philharmonic or even the Pops, but Boston can spoil a person and right now it seems enough that they're a professional outfit. They're doing Mahler's Symphony No. 5 tomorrow night, and even though it says SOLD OUT, Rodney knows from long experience that it's always easy to get a single ticket. A few clicks on the box office software and he's reserved his seat, and he falls asleep feeling wonderfully self-satisfied.

8

When Rodney knocks on Elizabeth's door on his way to the SGC the next morning, and gets no answer, he wonders if she ever comes back to the hotel at all. The television's still on in Sheppard's room. Rodney hesitates in front of the door and thinks about knocking, but he isn't sure what to say; he doesn't want it to look like he's rubbing it in that Sheppard's not currently welcome at Cheyenne Mountain. With a sigh, he turns and leaves.

He spends the day rejecting scientists—honestly, are these the best people they can come up with?—and then heads back to the Broadmoor for a shower and a shave. He can't bear to wear a tie, but he feels the need to dress up a little as a mark of musical respect, and so he puts on a button-down shirt and a sports jacket.

He's almost ready to go when there's a knock at the door, and he's pretty sure he didn't order anything for tonight, but this is a good hotel, and it occurs to him that they might be anticipating his habits. They're not.

Sheppard takes him in at a glance, and something in his face changes. "You're going out," Sheppard says, and Rodney's surprised before he realizes that Sheppard certainly knows him well enough to recognize that he's dressed unusually for him—neither for work nor for home.

"Yes," Rodney says, frowning, and last night, he'd imagined telling Sheppard that he was going out, and he'd felt vaguely smug about it, because he'd clearly figured out something to do with himself in Colorado Springs where Major Popular, Hip, and Good-Looking clearly hadn't. But he doesn't feel smug; he feels guilty. "I'm, uh," Rodney says, and his hands are moving fruitlessly in the air, trying to convey the no-big-deal-ness of it, the really-very-pathetic-ness, "I got myself a ticket to the symphony. They're doing Mahler's Symphony No. 5 ."

"Oh," Sheppard says, and Rodney recognizes that expression; he saw it in the mirror somewhere between Sheppard's explanation of an I-formation and a sack. "Cool. Have a good time," he says, and turns—

"Was there something...?" Rodney begins uncertainly.

"No, no; never mind," Sheppard says, and goes back to his room.

9

The terrifyingly named "Pikes Peak Cultural Center" turns out to be a real concert hall, and a swift glance at the architecture leads Rodney to believe that it was designed by somebody who actually understood acoustics. He's surprised by the claustrophobia he feels among the crowd milling in the red-carpeted lobby; it's been a long time since he's been among so many people. Still, he reminds himself that this is what he came for: he's here to be part of an audience. He knows that there's something about being in a room full of hushed, silently-breathing people that moves the experience of symphonic music from the wondrous to the sublime, and he can feel excitement surging through his nerves just from hearing the orchestra tune up. His seat is at the end of an aisle, so he loiters around the hall, idly reading the musicians' biographies in the program—half are from Tanglewood, which is reassuring—until the row is full and everyone is seated. Then he sits down, takes a breath, and closes his eyes.

There's applause as the curtain goes up, more applause as the conductor comes out, and then silence, punctuated by the occasional muted cough. A sole trumpeter plays the symphony's opening notes, and suddenly the tension is unbearable, in the orchestra, in the room, all of them holding their breath together and waiting for the first resounding, shuddering crash of instrumentation. And then it comes, wave after wave washing over him, through him, and it's all he can do to hold on against the tide of liveness, of life, pure, precise, mathematical energy, and not be swept away by the force of his own emotions.

10

The symphony leaves him weak and deeply gratified—positively post-coital—and on impulse, Rodney investigates the next evening's program, and buys a ticket when he discovers there's a guest pianist, in from the east. Rachmaninoff, but you can't have everything, and there's some Mozart and some Grieg, so what the hell. Patting the pocket containing the ticket, Rodney walks along the street outside the Cultural Center, and all of Colorado Springs' nightlife seems to be concentrated in this tiny downtown area: there are restaurants and bars and a movie theatre, and strolling couples and groups of friends huddled and laughing and arguing about where to go next, and Rodney feels like—not just a tourist, but an alien, gaping at the strange habits of the locals. He goes into a bistro and gets a table by the window, so that he can people-watch while he munches on his sandwich and drinks his beer.

He rides this state of dreamy contentedness all the way back to the Broadmoor, and it's only when the elevator discharges him on the 9th floor that he thinks about Sheppard. Suddenly he feels like he won't be able to stand it if he passes Sheppard's door and hears that the television's on, but then he does and it is.

Rodney stops and knocks, and when Sheppard opens the door, he's wearing jeans and sneakers and has done his hair in that strange style that Rodney has come to understand is intentional. "Hey there," Sheppard says, and leans against the door, "how was the music?"

"It was...extraordinarily good," Rodney replies, and that's an understatement, but he's not sure how to tell Sheppard how close he came to weeping, or how it made him feel like a whole person for the first time in a long time. "I bought a ticket for tomorrow, too," Rodney says, hand moving instinctively toward his pocket, and the idea's out before he's thought it through, "and I was thinking, you know, that maybe you'd want to come, have dinner and—"

Sheppard's expression is shuttered, but he's already shaking his head. "Thanks, but—I think I'm going to hop over to L.A.," and oh, huh, Sheppard seems to have found something to do after all, and Rodney has a quick pop-pop vision of the beach and the clubs on the Strip—that part of L.A., in other words, that isn't his L.A., which is Pasadena and Cal Tech and the Pie 'n' Burger. But the vision winks out of existence when Sheppard scrubs tiredly at his face and mutters, "Ford's got a cousin who lives there, so I figure, I might as well go and see her. Tell her what I can tell her, which isn't much. Still," Sheppard adds with a shrug, "it's not like I'm doing anything."

This is an unexpected horror, and Rodney nods grimly; this isn't something he would wish on anyone. "When are you going?" Rodney asks, and Sheppard answers, "Tomorrow morning; it's a quick flight, one stop. I'll be back the next day," and Rodney nods and says, awkwardly, "Tell her, tell Ford's family that—you know. That we all—"

"Yeah," Sheppard says in a dark voice, and for a second it's as if they're not in the Broadmoor, not in Colorado, or on Earth, but they're back in the blue and silver halls of Atlantis. And their teammate is lost.

11

When Rodney wakes up the next morning, the rooms on either side of him are silent. His breakfast—oatmeal, omelette, fruit cup, carafe of coffee—arrives, and he eats it while surfing the morning news on his laptop. He spends the day at the SGC demanding to see the files they think they've vetted, and sure enough, they've discarded all the interesting candidates: Fields at Cal Tech, and Ben-Zvi from Fermilab, and that woman Wasser who was such a prodigy over at M.I.T. two years before he arrived and trumped all her records.

The only familiar faces at the SGC are unfriendly ones, people he pissed off two years ago and who now show him tight, thin-lipped smiles if they smile at all. He can't wait to escape back to the Broadmoor; more than that, he realizes, as he shoves his key card into the lock, he can't wait to get back to Atlantis. Weirdly, he misses Teyla; he misses his lab and his room with its narrow, twin bed and single flat pillow; he misses the city, his home.

He changes his clothes and goes straight downtown, getting a steak and a baked potato at a nearby restaurant before queuing up at the Cultural Center at a quarter to eight. This time, when the lights dim, a single spotlight comes up on a grand piano. Rodney patiently sits through the Rachmaninoff, but he has to close his eyes during the perfectly-executed Mozart, and he's ripped into pieces by the Grieg, and maybe it's knowing that Sheppard is safely a thousand miles away where he'll never see and never know, but this time, he lets himself shake.

12

He's not sure if it's the emotional hangover from the Grieg or the incipient hangover from all the beer he drank afterwards to steady himself, but he can't sleep, even though he's exhausted.

It's 4 a.m. when he finally gets out of bed and switches on the television. After that, he's asleep within minutes.

13

Rodney's hung over the next morning, and oddly, the low murmur of ESPN on his television seems to help. He can't really eat anything, but he manages to down a few cups of coffee and a couple bites of toast before heading over to the SGC. But it's not his day, because General Landry chooses this morning to request a meeting with Elizabeth and whatever staff she has available, and Elizabeth looks disappointed when she finds out that Major Sheppard has amscrayed and Dr. Beckett's still in Scotland and the utterly respectable and quiet-living Dr. Rodney McKay has chosen the night before to go on a bender. Still, Rodney shows up for moral support, and tries to project an air of utter reliability and extreme brilliance while Elizabeth articulates their specific needs vis a vis personnel and materiel. Still, when the meeting is over, he high-tails it back to the Broadmoor, where he throws up and then flops down on his bed, fully clothed, for a nap.

He awakes to the sound of sports from next door, and rolls out of bed without thinking. His head is rotten but clears a bit by the time he's at the door, and then he's moving down the too-bright hall.

When Sheppard answers the door, he's in his black sweats again, and he looks terrible—he's pale beneath the dark scruff of his beard, and he has dark circles around his eyes, like he hasn't slept since he left.

"You look like hell," Rodney says.

Sheppard groggily rubs one eye. "You don't look so good yourself," he says, and then squints narrowly at Rodney. "What happened to you?"

"I—" Rodney waves his hand tiredly; it's too much effort to explain. "Drinking."

"Well, that wasn't very smart," Sheppard drawls. "I thought you were supposed to be the smart one."

"Tell me about Ford's cousin," Rodney interrupts, and Sheppard's face changes, goes hard. Rodney pushes into the room in case Sheppard decides to shut the door on him. "Tell me," he repeats.

"It's nothing, her name's Lara, she's very nice," Sheppard says. "She thinks I'm responsible for what happened to Ford," he says, adding, almost angrily: "And I think she's right about that."

"Oh, please," Rodney says, rolling his eyes. "Try that on somebody who didn't spend the past year fighting space vampires with you."

"I came to Atlantis," Sheppard begins, sharp as glass, "with one commanding officer and one second lieutenant. You don't think it's strange that Colonel Sumner is dead and Ford is—" and Sheppard's hand jerks violently to show that he doesn't know what the hell Ford is. "You don't think that says something about me?"

And it's funny, but only then does Rodney feel the weight of his year's experience serving on the away team, because Sheppard is muscling him, getting into his space, like he just might punch him. And a year ago Rodney would have backed down from a physical confrontation, but now he finds himself getting right up in Sheppard's face and saying, with as much hostility as he can manage, "I know just what it says about you. I was there."

Something twitches in Sheppard's expression before he nails it down, and Rodney sighs and awkwardly raises a hand to pat his shoulder. But it's not enough—he knows that immediately; they both do—and so he slings his arm around Sheppard's neck and yanks him into the tightest hug of his life. Sheppard hugs him back so hard his ribs hurt, and Jesus, maybe it's just the last couple of days or the trauma of the whole last year, or maybe it's just that right now John Sheppard is the only part of Atlantis that he has, but Rodney can't let go of him.

It should be embarrassing, but it isn't. Sheppard doesn't let go, either.

Then it's like Sheppard reads his mind. "I want to go home."

"Yeah," Rodney says, and his chest hurts.

"I can't live here anymore. I'm not sure that I ever could."

"Yeah," Rodney says, and then Sheppard's pulling back, putting his hands on Rodney's shoulders and pushing them apart, and he's wearing an expression that Rodney's never seen before. It might be fear.

"What if they don't let me come back?" Sheppard asks in a barely-controlled voice.

Rodney can feel his eyes widening: that's a truly horrifying thought. "They wouldn't. They can't. I mean, you've got the—" and Rodney's waving his hand up and down; the gene, he means, but not just that; it's the whole genetically-advantaged-hot-flyboy-soldier-surviving-in-another-galaxy thing he means: Sheppard in his entirety.

"I go where they tell me," Sheppard says mechanically, but his eyes are saying no; no, I don't. "And I lost my commander and my subordinate officer both. They won't like that," and then he adds, with a hard cheerfulness, "They already don't like me—"

"Oh! Well!" Rodney explodes, "I wouldn't know anything about that," and Sheppard grins, and it's a rare enough event that a smile reaches Sheppard's eyes that Rodney stops to takes notice; it's oddly breathtaking. "The SGC, the military commanders, they don't know—" and Rodney doesn't have to spell it out: that we love the place, that it loves us, that it's home in a way that this planet never was , because Sheppard's already nodding seriously; he knows. "Believe me," Rodney adds, "they'll probably send you back just to spite you."

Sheppard's hands tighten on Rodney's shoulders. "But what if they don't?" and Rodney's served with Sheppard long enough to know that he's not a guy to waste time on pointless hypotheticals. This isn't a hypothetical question.

"They will," Rodney says, meeting his eye, and Sheppard knows him well enough to know that that means, I'll put you through the gate myself, if I have to, and Sheppard exhales a long breath, lets his shoulders relax, and nods; message understood. And then Sheppard's backing away nervously, one hand reaching up to rub at the weird spikes of his hair, and Rodney understands that they need to find their footing, get back on normal ground.

"So, uh...are you going downtown again?" Sheppard asks. That weather's really something, huh? How about them Oilers? "Another symphony or something?"

"No. Yes. I don't know," Rodney answers distractedly. "Why?"

Sheppard just shrugs, a long elegant thing. "I don't know. I thought maybe I'd come with."

"Oh. Well. I—I'll go find out what's playing."

14

Rodney groans when the Philarmonic's schedule comes up on his laptop screen. It's chamber music: a violin sonata by Beethoven, a sextet for piano, flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn by Poulenc, and a piano concerto by Shostakovich: great stuff, but not what he would have chosen. Rodney had been hoping for something with a lot of bang and flash, for Sheppard—Tchaikovsky's War of 1812, Grieg's Peer Gynt, Beethoven's Seventh. He hesitates, then thinks 'what the hell' and buys the tickets: if Sheppard really hates it, they can leave. He's about to push the laptop cover down when he has another thought, and runs a search for "Colorado" and "football." The University of Colorado seems to have a team, but a couple of clicks brings him to a team called the Denver Broncos, which he thinks he's heard of, and a professional team must be better than a college team, right?

The only tickets he can get are nearly a hundred and fifty dollars each, but what the hell, and he buys two seats for tomorrow afternoon's game. He doesn't think he'll be coming back to Earth again, so he might as well spend some of his entirely useless money and see what an American football game is like. Denver's only an hour away.

And Sheppard won't come back to Earth, either; Rodney knows this. Sheppard will risk anything except being left behind, and if Sheppard is lucky enough to get back home to Atlantis, he won't push his luck.

15

Sheppard surprises him by dressing for an evening out: he's wearing a crisp white button-down shirt and a black jacket over jeans and boots, and Rodney thinks he looks oddly like a country-western singer. Rodney takes him downtown to the strip of bars and restaurants near the cultural center; the trees, Rodney suddenly notices, have been wrapped with little white Christmas lights. Sheppard points to a warm-looking restaurant called La Palapa, but Rodney instantly vetoes Mexican, since they put lime in every damn thing. They compromise on Italian, order huge plates of pasta and a bottle of red wine—and Rodney's just about to tell Sheppard about the Broncos tickets when it suddenly seems weird that he bought them; Sheppard's definitely going to think it's weird.

"What?" Sheppard asks, looking up from where he's buttering his bread.

"Nothing," Rodney says, and twirls his fork in his spaghetti. Sheppard gives him a look but lets it go, instead telling him how he saw Elizabeth leave the hotel just before they did. She was—

"—dressed to kill, Rodney. I'm talking murder. Low-cut dress, spiky heels, you know—" and Sheppard raises his hands and traces out some indeterminate, indiscriminate shape. "I almost didn't recognize her."

"Well," Rodney says, ripping into the bread, "I guess it's going well, then."

Sheppard lifts both eyebrows. "Do you think? I would have said it wasn't going well at all."

16

Rodney drains the last of his wine in a hurry when he realizes the time; thankfully, the cultural center is just down the street. He hands Sheppard a ticket, and Sheppard seems suitably impressed with the red-carpeted lobby, the well-dressed clientele, the bar that's selling cappuccino and glasses of champagne and strawberries.

"Do we have good seats?" Sheppard asks once they enter the hall, and Rodney has to explain that this is music, not spectacle; it's about sound waves and their reflections, and from that vantage point, most of the seats here are good.

Rodney takes out his pen with the laser pointer on the end and directs Sheppard's attention to the strategically-placed diffusers, the large, hard reflectors. "There's maybe a hot spot or two, a dead spot or two, but this is really pretty good." Sheppard, he sees, is looking at his laser pointer and trying hard to suppress a smile. "No, seriously: the acoustics are everything," Rodney says, hastily flicking off the red light. "I usually listen with my eyes closed," and then he shoves the pen back into his pocket, and swiftly moves down the aisle to their seats.

Two on the aisle, and no sooner have they taken their seats than the house lights flash twice and then slowly go down. There's the familiar rustling and coughing as people get comfortable and go silent, and then a single violin plays the tense opening notes of the Beethoven, and beside him, Sheppard drops his hands onto the armrests of his red velvet chair, and closes his eyes, and Rodney half-expects the theatre to light up.

17

Sheppard quivers during the Beethoven, tilts his head curiously during the Poulenc, and looks riveted during the Shostakovich—which means he understands music after all, thank God. After the final, crashing chord, the audience erupts in applause, some leaping to their feet, as the pianist stands smugly, one hand on the piano, and acknowledges them. Rodney just sits there, weighed by memories—playing that third movement, over and over, in the summertime, with the windows open and Jeanie and her friends shrieking with laughter outside on the patio—until he comes to himself and turns to Sheppard, who's just sitting there quietly, too, as people stream up the aisle past him.

"That was great," Sheppard says in a hushed voice, and Rodney understands that impulse to be hushed; when you've heard something truly wonderful, you don't want it chased out of your head with noise and stupid chatter.

"Mmm." Rodney looks back at the now unlit stage, and the abandoned piano.

Sheppard doesn't rush him, but eventually they stand, drift up the aisle, drift up the street. Still speaking with muted voices, they decide not to have coffee, to just go back to the hotel. They end up back in Sheppard's room, and Rodney doesn't know how it happens, if he starts it or if Sheppard does, but somehow they move from awkward fidgeting and even more awkward conversation ("Thanks for—" "No, I'm glad you—" "I did, I really did,") to kissing awkwardly, and maybe it's Sheppard who starts it, because Sheppard's hand is hot on the back of his neck, and Sheppard's tongue is in his mouth, but it's Rodney who wraps his arms around Sheppard and anchors them together so that they can kiss and kiss without falling.

18

"This is a bad idea," Rodney mumbles, between kisses.

"Hi, I'm John Sheppard, have you met me?" and all right, yes, he has a point.

19

They kiss for a long time—first upright, then horizontally on John's neatly-made bed. John's mouth is unbelievably soft under his, and Rodney cups his face and lazily sucks his tongue. It reminds him of being in college and making out with someone and it taking forever because there was no guarantee that things were going to move to the next level; you were just grateful for what you got. Kissing John is like that, and it makes him feel warm and happy and strangely young. His fingers find the buttons of John's shirt and undo them so that Rodney can slide his hand over John's heart, stroke through his chest hair, gently tease his nipples into hardness.

It takes a long time for things to get carnal, but when it happens, it happens fast. Rodney's hips are suddenly snapping forward—Christ, he's hard, he has to—and right then, John twists his face away, panting. And then they're both writhing, shucking their clothes and trying to get skin against skin, at least in the important places. John lets out a little moan of frustration, but Rodney works well under pressure. He gets John's pants open and gropes John's cock slowly, kissing his jaw and paying attention, until he figures out what drives John crazy. Then he moves his hand and works those spots until John gasps, "Rodney! Jesus!" in a gratifyingly broken voice.

He supposes he should wait, but he can't wait: he's almost desperate to come. He rolls on top of John, kissing him and humping him, trying to bring himself off, and then suddenly John's hands are on him, pushing him onto his back and John's voice is saying, "Wait—hey—hang on. Christ, let me—-" and then there's a hot, wet mouth around his cock, and something important in his brain explodes.

20

Afterwards, they sprawl on the bed and pant up at the ceiling. Finally, John groans and forces himself to sit up; he looks, Rodney thinks, actually kind of irritated. "Jesus, are you good at everything?" John asks.

Rodney thinks about that. "Mostly, yes, actually," he says, and John rolls his eyes and shoves Rodney's shoulder hard when he gets up to go to the bathroom.

21

Rodney wonders if he should leave, if the etiquette here is to leave. But he doesn't want to leave if John doesn't want him to leave; actually, he doesn't want to leave even if John does want him to leave, but he will of course leave if that's what John wants. He runs through the various probabilities in his head: John wants him to go because it's awkward now, or for appearance's sake, or because the sex is over; John wants him to go because he wants more room to stretch out on the bed, or because it will be a good sign that Rodney's not codependent. Or—John will take it the wrong way if Rodney tries to go, will think Rodney's ashamed or repressed or has issues with sleeping with a man, which he totally doesn't. Or—John actually wants him to stay, maybe for a second round, to reciprocate the truly excellent head he just gave Rodney or for some other sexual purpose entirely, which Rodney is totally on board with; or maybe just to watch football or something. Rodney decides that his best position is sitting up on the bed; that way, he can pretend to be leaving, or just stretching, or—

John comes out of the bathroom, pauses by the bed, and idly scratches his neck. "What are you doing?"

There's only one good answer. "Nothing," Rodney replies, and John looks at him a moment, then shrugs, and switches off the bedside light. That's a good sign that John wants him to stay, because it'd be rude to expect him to find his way out in the dark. Sure enough, John pulls back the covers and gets into bed, and Rodney hesitates only briefly before doing the same. The pillow smells like John, and John's punching his pillow before tucking it under his head, and it's been a long, long time since he's shared a bed with anybody; a really damn long time.

"G'night," John mumbles, and Rodney hears himself say, in a voice that's way too loud, "Good night," and it all seems strangely anticlimactic until John slings a possessive arm across his chest. Rodney goes out like a light.

22

Rodney wakes up, by force of habit, at seven in the morning. He's warm, sweating a little, because he's all tangled up with John Sheppard, who's sleep-heavy and loose-limbed and snoring faintly. Rodney has to tilt his head to a weird angle to see John's face. He looks different—younger, and kind of sweeter than normal—and Rodney's not at all sure that he likes it: he misses John's irony and faint but constant tinge of hostility.

This lunatic is my best friend on this planet, he thinks, and instantly amends, or any other, and maybe that should worry him, but in fact, he finds it staggeringly reassuring, and closes his eyes again.

23

The next time he wakes up, John's awake too, blinking stupidly and still looking sleepy. "Hey," John says, in a scratchy morning voice. "Wow. I slept really well—" and Rodney blinks and jerks to look at the clock. It's nearly eleven, and kickoff's at one, and Denver's an hour away by car—God, he has to rent a—

"Get dressed," Rodney says, sitting up quickly. "Hurry."

But John just pushes himself up on his elbow and looks at him lazily, the covers pooling low. Rodney's eyes are drawn to where the arrow of hair on John's belly disappears below the white cotton sheet. "What's the rush?"

Rodney forces his eyes back to John's face, and is reassured to see irony and faint hostility back in full force. "We're going to Denver."

John rarely looks surprised, but he looks pretty surprised now. "We're going to Denver? Why?"

"Because," Rodney says haughtily, shoving off the covers off, "I am reliably informed that there is football there."

24

"Are you serious?" John asks, as Rodney searches for his clothes. "No, really," John says, banging on the bathroom door, "Rodney, are you serious?" and then again, in the elevator on the way to the lobby, "You're serious, right?"

25

The concierge gives him the key to a white Honda, though John manages to liberate it before he can get to the driver's side door. Sighing, Rodney resigns himself to the passenger seat.

John frowns down at the dashboard as he shoves the key in. "You got an automatic?"

"This is America. It's all they had."

"I hate automatics," John says, looking over his shoulder as he shoves the car into reverse. "They suck."

"Obviously, but beggars can't be—" and Rodney is flung back as John throws the car into drive. They pull out of the hotel parking lot with a screech of tires, and really, it feels just like home. "Slow down," he tells John, as John speeds up the ramp onto I-25 north. "No, really; you're going to get a ticket," and when John shoots him a wry, sideways glance, Rodney bursts out laughing. "Sorry, yes, go ahead. Floor it," he says, and John does.

26

John makes what mapquest tells him is an hour and eleven minute drive in forty-one minutes, grinning maniacally the whole way, the western sky above a near-electric blue. They see the stadium ten minutes before they actually reach it—it just keeps getting bigger—and when John finally begins the long, slow crawl around the gigantic parking lot, Rodney gets the first of the day's panic attacks. There are so many cars, in so many colors, and he supposes that living on a island in outer space with three hundred people for a year is bound to do something to one's sense of perception. John must feel it too, because on the third turn, he reaches out and puts his hand on Rodney's arm. "S'okay," John says softly, reassuringly, glancing over. "Breathe deep, hang on."

Rodney breathes deep and hangs on, and the panic passes: it's just a parking lot, it's just cars, just people. They find a space and begin the long hike toward the stadium, joining more and more people, more and more people, more and more until they're finally passing into the cavernous interior hallways. They stop at the box office and pick up the tickets Rodney's reserved ("I'm always serious," Rodney explains) and then move, as directed, toward the "green zone." Rodney insists upon snacks, so they stop at a refreshment stand and order beer, hot dogs, nachos, super pretzels, and a huge carton of popcorn. John pulls out his wallet and pays the girl behind the counter, then turns to a kid beside them who's unraveling a wad of crumpled dollar bills, and says, "You want popcorn?"

The kid looks up at John nervously, like he's a nut, which he is, and then John pulls a bunch of twenties out of his wallet. "Here," John says, "buy popcorn for your friends." The kid looks like he's about to run for it, because somebody probably told him not to take money from insane Air Force majors, so Rodney says, in an impatient tone the kid is sure to recognize as adult, "It's okay, you can take it. We're leaving the country soon."

27

Rodney sees a narrow strip of blue sky at the top of the concrete stairs, and then they're out, in the open air of the stadium—where Rodney gets his second panic attack. He's gone to professional hockey games before, but those stadiums hold maybe 20,000 people, tops. This must be four times that, he's never seen so many seats, so many people, and there's chatter and yelling and the loudest, most terrible organ music in the world—

"Rodney," and John's shifting the beer and the hot dogs in his arms, and his voice is worried. "Are you—"

"Yes, fine; I'm fine," Rodney says, and takes a deep breath. "It's probably just a blood sugar thing," he adds, ripping off a piece of super pretzel and shoving it into his mouth, which actually makes him feel better.

"Okay," John says, and when he shifts again, he says: "Because, you know, if you hate it, we can leave," and Rodney can see how hard it is for John to say that, because while he's managed to keep his face neutral, every muscle in his body is tensed with please, no, please, please, please.

"No, no, no," Rodney says, and John's body relaxes so fiercely that he nearly drops the beer and the hot dogs. "Let's find our seats," and now he's really glad that the only tickets they had left were expensive, because their seats are really good—at least judging by the increasingly envious looks of the people they're passing and the way John's almost bouncing on his toes.

"Okay, so look," John says, once they've found their seats and slotted their beers into the cupholders and put their food on the little overhang provided for their convenience, "football isn't as much about spectacle as it is about sound. Now if you look over there," and John's pointing at something, but Rodney has no idea how he's supposed to pick whatever-it-is out of that sea of people, "you'll see some speakers, just beneath the commentator's booth: they project sound waves over the crowd. Sometimes," John concludes earnestly, just as Rodney figures out he's being messed with, "I like to watch with my eyes closed," and then it's Rodney's turn to feign seriousness as he beats John around the shoulders and chest and yells, "God! You are such an asshole!" while John twists away, hands raised to protect his face, and laughs and laughs.

28

He likes it all much more than he expects to: sitting outside in the crisp air, eating hotdogs, drinking beer, the endless waiting for seven seconds of actual football action, watching John leap out of his seat and yell and wave his hands for reasons he doesn't quite understand. John is more than willing to explain himself, however, sketching the plays in the air with his hands, or diagramming them on a napkin with a felt-tipped pen. It's almost too much information, and Rodney tries to keep up with the flow of it, listening and nodding, nodding and listening—until it suddenly occurs to him that this must be what it's like to be on the receiving end of one of his own expository diatribes. He feels his mouth crook into a smile, and suddenly John's saying, "What? What?"

29

John buys more beer from a roving huckster lugging a cooler, and tips the delighted kid more than the price of the bottles, and Rodney takes a moment to mark this place, this moment, in his memory: the impressionist painting that is 80,000 people, the vibration of their stomping, cheering bodies, the crisp Colorado weather, that amazingly blue western sky. Because they'll never be here again, in this place, in this moment. Rodney's got his head tipped back and is watching a single puff of white cloud drift across the sky when suddenly John's looming over him, John and everyone else is the whole stadium. He scrambles to his feet—he's missed the first touchdown—but it doesn't matter: John is hugging him wildly, lifting him nearly off his feet, and the roar of 80,000 people sounds almost like music.

30

They wander the huge concrete halls of the stadium at halftime; it's a fairly new stadium and like a mall inside, with a couple of restaurants and all sorts of shops. John walks past a sports memorabilia store, then stops and does a double-take, and Rodney has just a moment to insist, "Oh, God, please—no shopping!" but John is already pushing through the glass door, and with a groan, Rodney follows.

John heads past the Broncos pennants and Broncos mugs and Broncos refrigerator magnets and Broncos sweatpants and shorts and t-shirts and signed footballs and, Jesus, snow globes, and goes straight to a wall of football jerseys. Every possible team in the history of the world seems to be represented, and Rodney's relieved that John at least seems to know what he wants, and so they won't be trapped here, endlessly browsing. John snags a long-sleeved maroon t-shirt off the wall—Boston College, number 22, which figures: Rodney's seen the damn Hail Mary videotape enough times to know that that's Flutie's number—takes it off the hanger, and throws it over his shoulder. Fine, great, they're done: let's go!—except apparently they aren't done, because John is frowning and flipping through the rest of the Boston shirts, and Rodney puts on a giant foam hand and begins theatrically tapping at his watch. John rolls his eyes but doesn't stop searching, and Rodney groans and turns to look at a table of impossibly tacky knick-knacks.

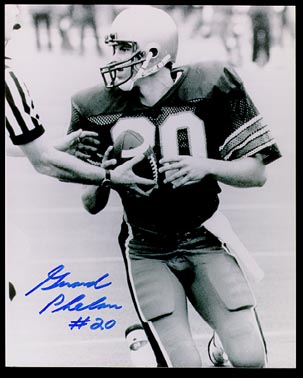

He hears John grunt in satisfaction, turns around, and gets a maroon t-shirt slapped onto his face. Growling, Rodney pulls it off and glares at John, who's already moving toward the cashiers and looking smug. Rodney looks down at the shirt in his hand—it's an Eagles shirt, number 20, size large—and follows John to the register.

"Is this supposed to be for me?" Rodney demands, and it comes out sounding pissier than he means it to; he's actually kind of touched to be on the team.

"Yep," John says, without looking at him. He takes the shirt back, puts it with the other, gets in line. "Call it a present."

"Flutie went to Canada, you know," Rodney says, which is what he always says when John goes on about the Hail Mary, except now it sounds different; now it sounds like a proposition. John shoots a look at him. Rodney has to look away. "Who's number 20?" he asks without turning back, but John doesn't answer, and a moment later, Rodney hears him being charming to the salesgirl, saying, "Yeah," and "No problem," and "No, I'll pay cash."

"Gerry Phelan," John says, when he turns away from the counter, and Rodney's about to say, "Who?" when the loudspeakers come on and announce that the second half's about to start. Outside, people are moving rapidly toward the bleachers with their food and beer, and Rodney's about to join the flow when John tugs him in the other direction.

"Uh, I'm pretty sure we're going the wrong way," Rodney says, but John is doggedly pulling him upstream, dodging and weaving through the crowd, and then John pulls him into the rapidly emptying men's room, and Rodney has a moment of thinking, stupidly, Oh, well, yes; it was a lot of beer, before John practically hurls him into a stall and shoves him up against the door, and Rodney only has a moment to blurt, "Wait, what are you—?" before one of John's hands is hot against his mouth, and the other is groping low in his pants, and John's whispering, "Shh," and biting his ear softly, "shut up," and then he's kissing Rodney's face and working his cock hard and fast. John's hand is tight, hot, slick, strong, and Rodney groans into John's palm as John coaxes his orgasm out of him ("C'mon, Rodney; c'mon, attaboy, there we go—") in several violent-sharp spurts.

Afterwards, Rodney leans back against the flimsy partition, quietly panting, as John pulls a wad of toilet paper off the roll. But this isn't over; this is so not over. Rodney raises both hands, grabs John by the ears and pulls him in for a kiss. John makes a soft noise of surprise, and then groans and opens his mouth when Rodney keeps right on kissing him. John lets Rodney roll him back against the door and spreads his legs when Rodney nudges between them with his knee. Rodney blindly manages to open the button of John's jeans and tug down the zipper, and then he's shoving his hand into John's pants. John moans desperately into his mouth and pushes his dick into Rodney's hands, and when he comes, Rodney keeps kissing him: when he comes, and for a good while after.

31

John sits in blissed-out stupefaction for the rest of the game, though whether it's the football or the beer or the sex, Rodney can't say. He himself is enjoying his own state of blissed-out stupefaction, which is definitely sex-related: he's had two sensational orgasms in the space of 24 hours, breaking a streak of—oh, really longer than is worth thinking about. The Broncos had managed to score another touchdown while they were jerking each other off in the men's room, though John didn't seem to mind having missed it. ("That's cool," John said, and waved for the roving beer guy to bring him another beer.) The universe obliges John Sheppard by letting the Broncos score one more time in the second half, though it fails to provide the Hail Mary pass that Rodney is half-expecting.

Still, it seems to be a good enough game and when it ends, John is grinning goofily and generally looking happier than Rodney's ever seen him look. John hands him the car keys and sits, slouched and relaxed, in the passenger seat, head lolling against the headrest while Rodney negotiates the horrible, post-game traffic. "Do you remember when—" and "That last touchdown, that play that Preston made, Jesus—" and Rodney smirks and nods, feeling smug but not really paying attention to the details. Instead, he listens to John's voice, the soft rumble of it, the ebb and flow of his enthusiasm—and when John stops talking, it's like someone's turned off the radio.

Rodney shoots a quick look over into the passenger seat. John's watching him silently, thoughtfully, and then he says, to Rodney's complete and utter surprise, "Where's your cat?"

Rodney shoots a boggle-eyed look at him. "What?"

"Your cat," John repeats. "The cat in the picture. Is she dead?"

"He," Rodney says, sharply correcting him, "and no, he isn't dead! What makes you say a thing like that?"

"Well, he could be dead," John points out, reasonably. "It could be an old picture."

"Well, he's not. He's fine," Rodney says, realizing a moment later that of course he has no idea if Kepler is fine or not.

"So where is he?" John asks.

"He's with my neighbor, my old neighbor, in the complex where I used to—what does it matter?"

"In Colorado Springs?" John presses.

"No, in Fountain: I wanted to live as close to my lab as—seriously, why does it matter?"

John says, "We could go see him," and something really furious rises up in Rodney's gut, because honestly, he went out of his way to make this a nice day for John, and this asshole is mocking him. Rodney tears his eyes from the road to give John a hard stare—but John just blinks and says, "Hey, we don't have to if you don't want to," and Rodney suddenly understands that John is perfectly serious.

Still, he can't quite tamp down the furious thing inside him. "Why the hell would you want to see my cat?" and John thoughtfully waggles his head and then says, finally, "I don't know. You brought his picture to Atlantis. I thought you'd want to," and maybe it's because John's just raised the idea that Kepler could be dead, but Rodney suddenly really does want to see his cat, and so he stays on 25 south and heads for Fountain.

32

He has his old key to the building, but he buzzes anyway, because there's no point in going up if Sarah's not home. But a moment later, the intercom blares static and a sing-songy voice says, "Who is it?" and Rodney clears his throat and says, "It's Rodney McKay," and then, when there's no answer for a moment: "Your neighbor? From 3B? You've got my—"

"Rodney McKay? Wow. What are you—" and then there's a buzz, and Sarah's saying come up, come on up, and so Rodney pushes through the door. John follows him across the lobby to the elevator.

They have to pass his apartment to get to Sarah's, and Rodney walks past it without letting his eyes so much as waver, but John—John is Major John Sheppard of the United States Air Force, and unfortunately not at all stupid, and so he stops when they pass 3B and says, "Hey, was this your apartment?" A moment later, John is leaning forward, having spotted the tiny lettering in the nameplate of the brass knocker, and then John turns around and glares at him. "You still live here?"

Rodney stops, sighs, turns around. "I still pay rent. Or the bank does."

John turns around again and stares at the door like he's never seen a door before. Or like he's Superman and he can see straight through it. "But why," John begins, gesticulating toward the apartment, "why didn't you—?" and it's a reasonable question; he never thought to come here, not once. Maybe because even in his own fabricated reality version of this place, there were no messages on his answering machine: just corn chips and television. And while corn chips and television are mighty fine things, they somehow don't seem like quite enough anymore. What exactly did he leave behind? His collection of science fiction paperbacks? His old physics club t-shirts?

"There's nothing—" Rodney begins, and then turns the words around. "There isn't anything," and then he's walking fast down the hallway. Sarah Mendelsohn's in 3H, and Rodney rings the bell. There is a sound of yowling cats, and Rodney grins stupidly, because one of them is Kepler, he's absolutely sure of it: he'd know that ornery screech anywhere. And then the lock is turning and the apartment door is opening—and boy, Sarah looks good, but then, she always did.

Rodney says, "Hi, Sarah," and Sarah grins and cocks one hip and says, "Hey there, Rodney. Come on in," and for a moment, Rodney has déjà vu, because he could swear that Sarah's coming on to him a little, just like in his fabricated reality scenario, except then of course she says, "Who's your friend?" and right, yes: earth is still on its axis, never mind. "This is," Rodney begins, but then he stops, because there's Kepler, all four feet firmly planted and glaring defiantly at him from in front of the sofa, and Rodney knows that look, it's: you are such an asshole, you said you'd be home hours ago . Vaguely, he hears John say, "Hi, I'm John," and Sarah saying, in that weird, flirtatious voice, "Hi." Rodney rolls his eyes.

"Okay, look, I'm sorry," he tells Kepler, "but you're a cat, and I'm committed to having you fed on a regular basis, but I'm not letting my life revolve around you," but Kepler isn't buying this, not at all. "You've got a nice place here, you like Sarah and Percy," Percy was Sarah's cat, "—so you're fine," Rodney says, jerking a hand out toward him, "in fact, you're fat, so don't start with me. I come all this way to see you and what do I get? Cat attitude," and this line of reasoning seems to work, or maybe Kepler's just nostalgic for Rodney's crankiness, because all of a sudden he's coming over, and rising up on his back legs and pawing at Rodney's pants, and Rodney sighs and bends to lift his fat ass off the floor. "C'mere, you stupid—" Rodney grumbles, though this really isn't fair: Kepler's the smartest cat he knows, and more intelligent than many people he's worked with. And Kepler's warm and heavy and doing that weird thing he does sometimes where he tries to nurse at Rodney's left earlobe, and Rodney twists his head away and says, "Stop it, you crazy—" but he can't help but hug the cat tight.

"Yeah, I think he misses you," Sarah says, with a sigh. "He keeps thinking that maybe tonight you'll come home from the lab," and then she's explaining to John that she's a doctor, and that she—like most of the people in the building—works over at the Cheyenne Mountain complex, in the infirmary, and ha, she used to think that doctors were insanely obsessive workaholics, but then (and now she's smirking at Rodney) she began hanging out with physicists. "Doctors are relaxed," Sarah tells John, making it seem like a come-on.

"Uh-huh," John says, noncommittally, and then he's coming over and tilting his head sideways and peering down at the cat, and Rodney says, "Kepler, this is John," and then, the most amazing thing happens: Kepler glares at John resentfully, and John arches an eyebrow and briefly lets his faint air of hostility become real hostility, and then Kepler slowly unflattens his ears. "C'mere, let me have him," John says, and opens his hands. Rodney's expecting Kepler to freak out and attack, but Kepler just hangs limply and lets himself be given over to John. John crooks a long finger and skritches him first under his chin and then behind his ear, and Jesus, Rodney can hear the blissed-out purring from here. "You psyched out my cat," Rodney says, almost accusingly.

John smiles faintly and shrugs. "He seems pretty good-natured," which is a preposterous thing to say about Kepler, who has five kinds of personality disorder, but then John says something even more ridiculous: "Let's spring him."

"What?"

"Spring him. Take him with us. Take him home," John says, and this last is directed in a casually pointed way toward Sarah, who visibly deflates—and honest to God, could this day get any better?

33

"Are you crazy?" Rodney asks, even as he's throwing Kepler's bowl into a plastic bag. "This is crazy," he says. "No, really. John. This is—" but John's zipping the cat into his jacket until only his furry head is visible, and geez, it's pretty clear who's alpha cat now. Rodney asks questions that start, "How are we going to—?" and "What if we get—?" and "How can we possibly—?" but John just smiles and snags the car keys from his fingers and says, "I've got some ideas."

34

They arrive back at the hotel overburdened with stuff: they've got their souvenir t-shirts and the cat bowl and a portable litter-box and a bag of litter and a sack of cat food. John is also lugging an acoustic guitar and two carrying cases that he's just bought: one, a soft case of black nylon, the other a hard case lined with red velvet. ("I didn't know you played guitar," Rodney said. "I don't," John replied, with a grin, "but I look like I do, don't I?" Kepler yowled unhappily.)

They manage to get Rodney's door open and lug all their stuff inside. John unzips his jacket and Kepler springs down to the floor and begins to explore the room, nosing into the bags and Rodney's shoes and eventually settling down happily on top of a pair of corduroy pants. John puts out bowls of food and water while Rodney sets up the portable litter-box in the bathroom—and then suddenly, there's an angry knocking on the door, and Rodney and John jerk up to look at each other, and Rodney can see that they're both having the same reaction: holy shit, it's the cat police!

"Hang on a second," Rodney yells, while they work in silent unison to get Kepler and his stuff shoved into the bathroom. Then Rodney takes a deep breath and opens the door, while John lounges near the desk, apparently trying to look casual.

It's Beckett, looking flustered. "Rodney," he says, "where on earth have you—" and just then, Beckett sees John. "Major! You've got to get to base: they've been looking and looking for you! Didn't you get their messages?"

John frowns and slowly shakes his head. "No," he says. "I haven't been in my room. What's going on?"

"I'm not rightly sure," Beckett replies, "except Elizabeth sent me over to bang on your door personally. Whatever it is, though, it's important: she was meeting with all the top military brass, and you could cut the tension in there with a knife, I swear to God."

Rodney's about to protest that it's late, it's dark, whatever it is, it can wait until tomorrow, surely, when John says, tiredly, "Okay. Let me just put on my uniform." And it's funny, but two days ago Rodney wouldn't have seen the live-wire tension underneath John's pose of ironic exhaustion, but now he does see it: sees both tension and fear.

"I'll come with you," Rodney says, and John pauses, halfway out the door, and nods sharply before disappearing. Rodney grabs his own regulation gear out of the closet, waves Beckett toward a chair, and opens the bathroom door—forgetting entirely about Kepler, who shoots out of the bathroom like a bat out of hell. Rodney whirls around, but Beckett is already leaning forward and making kissy-faces at the cat, who is regarding him with disdain.

"Puss, puss," Beckett says, extending his hand and snapping his fingers. "Aren't you a pretty kitty?" and Rodney sighs and groans and goes to get changed.

35

John is an entirely different person on the way back to Cheyenne Mountain: he's in uniform, straight-backed and hard-faced and entirely unlike the lazy, joshing slacker who jerked him off in the men's room and kidnapped his cat. In fact, if Kepler were to see the barely-suppressed hostility in John's eyes, in his flared nostrils and the defiant jut of his chin, he would hide under the bed and never come out. Rodney hopes it has the same effect on the SGC brass.

Once they're inside the mountain, Beckett leads the way, and John follows, and Rodney brings up the rear, and it feels eerily like they're escorting John to a court martial, or a firing squad, or his own funeral. Beckett knocks softly on a door, which is opened by a marine, and Beckett's right: the circular arch of the conference table is full of the Pentagon's top brass and the SGC's top generals. John shoots a single, swift glance at Rodney and looks away just as fast, but Rodney hears John's tense voice in his head just as clearly as if he'd spoken aloud: McKay, you bastard, if this goes the wrong way, you've got to help me, you promised, and Rodney nods sharply and immediately starts planning scenarios.

"Major Sheppard," General Landry drawls, "so glad you found time to join us."

Sheppard shows him a faint, crooked smile. "Well, the Broncos were playing, sir," and that gets him a few low chuckles around the room.

"Hm, yes, I see," Landry replies, and then he turns and says, "General O'Neill, would you kindly explain the situation to Major Sheppard."

"Yeah, sure," General O'Neill says, and slouches back in his chair. "Major, you should know that your apparent inability to follow a proper chain of command has provided us all with many hours of fun-filled entertainment. You should also know," and something in the General's voice goes airy, and Rodney instinctively tenses for bad news, "that the decision was very nearly taken to remove you from the Atlantis expedition entirely," and Rodney feels simultaneously furious and overjoyed, because a decision was nearly taken, which of course means it wasn't. "However," General O'Neill adds in that same, airy voice, "the point was then made that this would only mean putting you under some other poor bastard's command, probably someplace where those very interesting genetics of yours would be of no use at all." Suddenly General O'Neill sits up and leans forward, lacing his fingers together. "My own personal opinion is that the only way to deal with soldiers like you is to promote them until they have to take themselves seriously," and wait, did he say—? "Which sucks, by the way."

"Sir?" John sounds like he's strangling. "I'm sorry, did you say—?" Rodney jerks to stare at Elizabeth, who's sitting there, looking exhausted and smug. Rodney lets the question show on his face—"For real?"—and watches her nod.

General O'Neill shrugs, reaches forward for a small pretzel, and tosses it into his mouth. "Yeah. We're promoting you to Lieutenant Colonel and officially appointing you the military commander of Atlantis. Wacky world, isn't it?"

36

They all four of them end up back in the hotel bar, celebrating late into the night with bottle after bottle of champagne and plate after plate of terrible bar food, and when John opens his wallet at the end of the night and gives all his money to their waiter, everyone assumes that he's drunk.

Rodney knows better.

37

Rodney and Carson half-carry, half-drag John back up to his room, pull off his shoes, and dump him on his bed while Elizabeth stands there, still holding a glass of champagne, and says, "Goodnight, Colonel!" Then they all tromp back into the hall, wish each other good night, and let themselves into rooms 912, 914, and 918.

Rodney has a moment of something very near to joy when he's greeted by his cat, and he bends and hugs Kepler to his chest for a long moment before dropping him onto the bed and going to change into a t-shirt and shorts. He puts on the Boston Eagles t-shirt John bought him, and then frowns, goes to his laptop, and googles "Gerry Phelan number 20." He feels a lump rise in his throat at the first link that comes up: "Forever And Ever, The Pass: Flutie to Phelan still a miracle 15 years later," and when he clicks on the article, there's a picture with a caption: "Gerard Phelan, the kid who caught the most famous hail-mary in college football."

Rodney slowly shuts the laptop. Behind him, Kepler is pacing back and forth across the bed, testing his claws on the bedspread, though he stretches out contentedly when Rodney gets under the covers and turns off the light.

It isn't more than 20 minutes later when there's a soft knock at the door, and Rodney comes instantly awake and opens his eyes in the dark. He scrambles out of bed—vaguely processing a pissed-off 'meow' from Kepler, who's been knocked onto the floor—opens the door, and pulls John inside. The door's not even fully shut when John's on him, groping and kissing and murmuring, "Rodney, Jesus, can you believe—" and yes, yes, Rodney can believe it, except no, he can't believe any of this, none of this can be happening, and Rodney's got John's erection in his hand and he's kind of using it to steer him back toward the bed.

Rodney pushes John down onto his back and climbs on top of him, greedily tugging at his thick spiky hair and pushing his tongue deep into John's mouth. When they finally break apart, John grabs Rodney's shoulder hard, yanks his head down, and whispers furiously into his ear, "I want you to fuck me." Rodney groans aloud, because he wants that so much—he wants to fuck John Sheppard into next week, into the next galaxy. But John quickly presses his hand to Rodney's mouth to stifle the sound, and then gingerly removes it again.

"Shh. The walls here are thin," John says, and kisses him.

Rodney laughs softly, and then kisses him back. "Yes, yes, I know."

The End